It turns out that immigration may be good for the environment

In a paper published in Population and Environment, I assessed the impact of immigration on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions across U.S. states.

Immigrants form a crucial part of American society. They make up more than 13% of the US population as a whole and are anticipated to contribute 88% to population growth. Immigration can alter the physical, social, cultural, and economic landscape of host nations and significantly boost productivity, economic growth, and the vitality of labor markets.

Immigration is politically and socially controversial. Immigrants have historically been blamed for being unable to assimilate, responsible for lowering wages, displacing native people from their employment, and disproportionately utilizing social, health, and educational services. More recently, as environmental concerns gained popularity, they were blamed for climate change arising from the population growth in host nations.

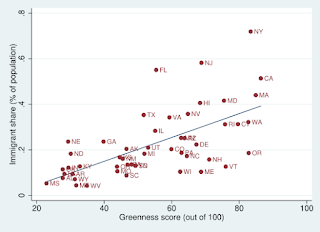

A preliminary look at the data shows that states with a higher proportion of immigrants are expected to have better environmental conditions.

Several theories help explain the potential environmental impact of immigration, including but not limited to environmental justice and social disorganization. For instance, an unsettling correlation between poor groups, such as immigrant populations, and regional environmental quality has been revealed by seminal environmental justice studies.

Minorities of color in America have long suffered from disproportionately high levels of pollution and toxic waste in their neighborhoods. This problem, however, does not only affect Americans. For instance, it has been discovered that immigrant neighborhoods in France are disproportionately exposed to hazardous facilities and incinerators. Such exposure is thought to have institutional racism at its core. As a result, low-income areas with a sizable minority populace that is underrepresented owing to immigrant status or socioeconomic class provide ideal targets for hazardous and polluting facilities.

Social disorganization is another theorized factor potentially contributing to immigrants’ disproportionate exposure to various social and environmental problems. It arises when immigration flows can alter the mix of cultures, languages, and backgrounds of a community significantly enough to result in a less cohesive society. Communities become so racially and ethnically heterogeneous that social ties, bonds, and controls become too weak to allow them to effectively organize, prevent, or drive out environmental risk. However, relevant empirical evidence suggests that immigrant communities may be more revitalizing than disorganizing due to strengthened social control and a stronger unifying bond. This could be the result of immigrants choosing to settle in locations that provide immediate access to a large network of co-ethnic friends and relatives. Thus, in contrast to social disorganization, the social cohesiveness of immigrant communities can represent an important asset in effectively combating local sources of pollution.

Result #1

Larger populations across U.S. states increase GHG emissions, whereas a larger share of immigrants decreases GHG emissions.

Result #2

U.S. states with lower GHG emissions attract more immigrants.

This research highlights the potential role of air quality as an environmental amenity and the potential role of toxic dumps and high pollution as environmental disamenities. It also points out that immigrants have less extravagant consumption habits than their native-born counterparts. Immigrants’ choices, whether driven by genuine concerns about the environment or by financial commitments and constraints, are likely beneficial to the environment.

It is however unclear whether such habits persist down the generations or whether offspring of foreign-born citizens who are born and nurtured in the United States will likely integrate and take on the wasteful purchasing habits of their native counterparts. Evidence from France indicates that immigrants, regardless of age, eat less than their native counterparts on average, however, data from Canada indicates that the consumption patterns of immigrants’ children are comparable to those of their native counterparts in a number of categories.

In conclusion, this research provides evidence dispelling prior requests for immigration restrictions based on environmental concerns.

Comments

Post a Comment